Classical Inquiries

Classical Inquiries (CI) is an online, rapid-publication project of Harvard’s Center for Hellenic Studies, devoted to sharing some of the latest thinking on the ancient world with researchers and the general public.Recent articles

Death of a ram, death of Patroklos

2020.07.31 | By Gregory Nagy

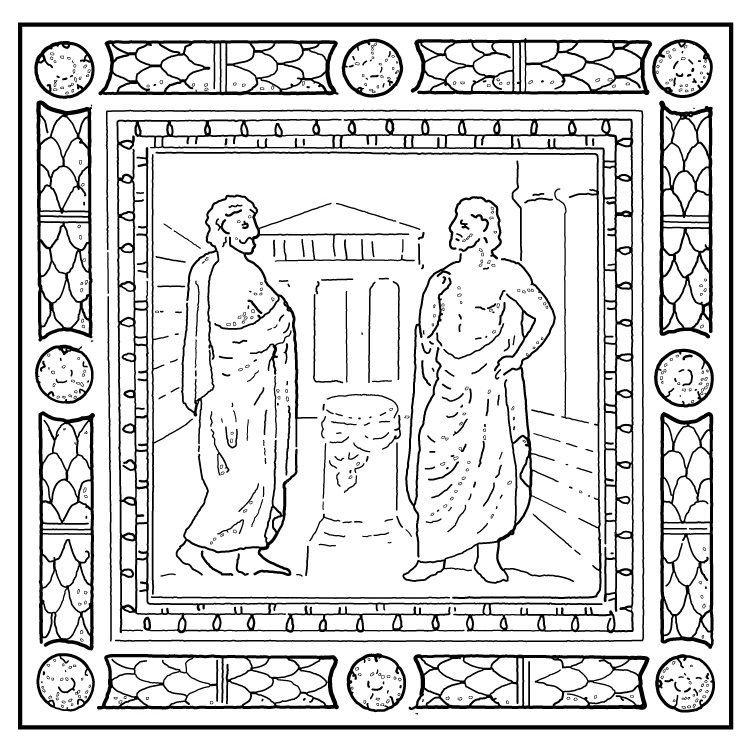

A picture is worth a thousand words. That popular adage fits, to my mind, the picture I have chosen for the cover of my essay here—the word-count for which even exceeds a thousand, though not by much. The picture is a line drawing of an ancient vase-painting. The camera of the mind’s eye is zooming in—on a sheep’s head. It is the head of a ram, a dead ram. His throat has been slit, with blood flowing from the gaping wedge where the cut had been made, evidently by way of a sacrificial knife. The blood is not visible in the black-and-white line drawing, but it is clearly there in the original painting, which also shows—as we see even in the line drawing—how the left eye of the ram is looking directly into the eye of the viewer. It is the look of the dead, with eyeballs rolled up, as it were, in a death-stare. This sacrificial ram, as we will see, stands for Patroklos, who dies as a sacrificial body-double of Achilles in the Homeric Iliad.

[Essay continues here…]Apollonius of Rhodes and Homeric Anger

2020.07.24 | By Stan Burgess

§0. There have been many recent studies of various aspects of anger in Greek culture, from Homer through the Hellenistic period, and beyond. However few have examined the role anger plays in the Argonautica. There right away a striking curiosity concerning anger stands out. Apollonius of Rhodes avoids the most common term of his day for anger, ὀργή. Through the Classical period and into the Hellenistic, ὀργή became the predominant word for anger. In fact, it is this word and concept for anger that Aristotle analyzes and defines in the Rhetoric. When the Stoics in the Hellenistic period write about anger, it is ὀργή that is their primary concern. But not once does it occur in the Argonautica, which otherwise is replete with anger. Is this perhaps to avoid anachronism? The term ὀργή does not occur at all in Homeric epic either. Since Apollonius’s setting is in the Heroic age, does he avoid the term to make the Argonautica seem archaic and epic, and/or to fit the genre, even though he avoids many other epic conventions? To the extent that the Argonautica also cloaks concerns of his own Hellenistic culture in epic dress, his preference for epic anger vocabulary, the nouns μῆνις, χόλος, and κότος, and their denominative verb forms, invites exploration. The rich specificity of each of these terms provides Apollonius a way to frame different levels of social severity inherent in the situations in which the terms occur. One size doesn’t fit all.

[Essay continues here…]About a scene pictured on the Bronze Doors of the Supreme Court, already pictured once upon a time on the Shield of Achilles

2020.07.24 | By Gregory Nagy

§0. At the very beginning of my Introduction to The Ancient Greek Hero in 24 Hours, at 00§1, where I talk about the “great books” of Greek literature that I will be analyzing, I say that I will also be showing pictures, taken mostly from ancient Greek vase paintings. As I now look back at the pictures in that book, first published online in 2013, I keep thinking of other relevant pictures I could have shown—but which I had already had a chance to show in another book of mine, Homer the Classic, first published online in 2009. In this essay, I highlight the relevance of one such picture. It is a scene of litigation between two heroes, pictured on the Bronze Doors of the Supreme Court. And this scene, which is part of set of eight scenes picturing the Rule of Law as it evolved through the ages, was inspired by a scene described in the Homeric Iliad. That Homeric scene, as we will see, was all about an all-powerful idea: human life is priceless. That is, you cannot put a price on human life. Such an idea, endangered once again in our own time, is at stake already in the world of Achilles.

[Essay continues here…]For anyone tempted to read the Homeric Iliad, all of it, in translation: some words about a book that can help with getting started

2020.07.17 | By Gregory Nagy

§0. In this brief essay, I talk about a book that can help get you started if you wish to make a personal commitment to read the Homeric Iliad, all of it, in translation. It is a book of mine that was first published in 2013 by The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press under the title The Ancient Greek Hero in 24 Hours. Thanks to the Press, this book is also available online, for free. Alternatively, readers can order, from Harvard University Press, an abridged second edition of the printed version, published as a paperback in 2020. And how is this book helpful to those who are tempted to read the Iliad of Homer? In my essay, I claim that the illustration on the cover of the book, in both the printed and the online versions, offers a good answer. To say it another way: sometimes you can in fact judge a book by its cover.

[Essay continues here…]On some mystifying language used by Pausanias in referring to the Eleusinian Mysteries

2020.07.10 | By Gregory Nagy

§0. I have run into a problem in trying to come up with an adequate translation of Pausanias when he talks about the Eleusinian Mysteries. Part of the problem, I think, is that Pausanias himself is mystifying in his language about the Mysteries. He seems guarded about giving the impression that he is in any way about to reveal to his readers whatever was periodically being revealed to initiates in the Great Hall of Initiation at Eleusis. My purpose in this brief essay is not to attempt a reconstruction of what was actually revealed. Nor do I aim to solve the mystery of what Pausanias thinks is the essence of the Mysteries—any more than I would hope to understand the Eleusinian Mysteries as represented by Dirck van Baburen in his painting Mistérios Eleusinos, dating from the seventeenth century of our era, a suitably dark copy of which is featured as the cover illustration of my post here. No, all I intend to do here, as I already said, is to produce an adequate translation of the mystifying language used by Pausanias in his reference to the Mysteries. But I must add that my translation is not meant to be mystifying: rather, it is meant to convey the actual language of mystification that is being used here by Pausanias.

[Essay continues here…]Older Posts →Insomnia, Homer, taut sails, by Osip Mandelshtam

Translated by Philip Nikolayev Insomnia, Homer, taut sails: my lips have lisped Down to the middle the detailed list of ships, That long brood and angular train of cranes That rose above Hellas once on wings of waves. A wedge of cranes into far foreign lands – Divine white froth forming upon kings’ heads

[Essay continues here…]

See AWOL's full List of Open Access Journals in Ancient Studies

Stumble It!

Stumble It!

No comments:

Post a Comment